Many companies have been astonished at the difficulty and cost of renewing their Directors and Officers insurance in the past year. This is a trend that we view as likely to continue, particularly at the top end of the market, as insurers face an uncertain and increasingly risky claims environment – while at the same time, capacity in the London insurance market continues to tighten (as Lloyd’s imposes solvency controls upon syndicates).

We have been working with a number of large companies that have actively explored ways to manage or limit their D&O insurance expenditure. We discuss some of these in this article.

What is happening?

Many companies are experiencing ‘shock’ D&O premium increases that in some instances have been multiples of their previous year’s premiums. Dual listed companies have been particularly affected as insurers perceive greater risks of claims in Australia. New Zealand companies are also experiencing substantial premium increases and some are having difficulty arranging replacement cover where their insurers have left the D&O market.

There are a number of reasons for this, which together create a ‘perfect storm’ in the D&O market.

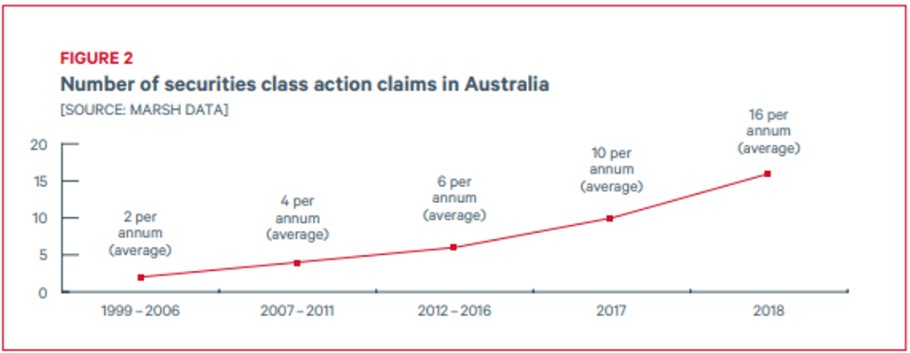

The first reason is the exponential growth in the number and size of funded securities claims that has been experienced in Australia in recent years. Insurers rely upon historical trends and informed assumptions for actuarial calculations that inform their estimates of likely claims, to set premiums. They have experienced a significant increase in the number of securities claims against directors brought as group or ‘class’ actions on behalf of large numbers of affected investors, often funded by third party litigation funders and supported by specialist lawyers. In a recent article co-published by our firm, insurance broker Marsh and the Institute of Directors, the following table was used to illustrate the exponential nature of the increase in claims:

The cost of dealing with these claims has increased proportionately, so premium costs necessarily rise. The known rise in claims costs is exacerbated by insurers’ increasing uncertainty as to what the future holds, which has caused them to increase premiums further.

A second reason is a D&O premium base that historically has not kept up with claims costs. D&O insurance was traditionally a relatively low-cost addition to a company’s suite of policies that was offered as part of an overall package. In the distant past, directors were obliged to pay for the cost of this insurance themselves, which encouraged insurers to offer it at a very low cost on the basis that they would earn their profits from the premiums for the wider policy suite. Insurers now have no option but to charge D&O premiums that fairly reflect the risk of claims and losses.

A third reason is insurers’ apprehension that the New Zealand legal environment is beginning to adopt some of the features of the Australian environment that has resulted in increased numbers of group litigation proceedings and securities claims. The New Zealand Supreme Court recently approved ‘opt out’ representative or ‘class’ actions in which a law firm and a litigation funder may act on behalf of a large group of investors or other affected persons without their express consent, provided they do not object, thus making it considerably easier to bring a claim on behalf of a large number of people with the same interest in a claim. These actions lend themselves particularly to securities claims in which investors may have been misled, or continuous disclosure claims in which investors may have overpaid or been underpaid for shares. In addition, litigation funding by third parties for a share of the proceeds of an action is increasingly accepted. We are beginning to see professional litigation funders being increasingly active, although we have not seen firms of class action lawyers emerge with the level of sophistication that exists in Australia.

While class actions in New Zealand remain relatively rare, they are increasing in number. In recent years, there have been group actions against the directors of a carpet manufacturer, Feltex; an insurer, Southern Response; a building supply company, James Hardie; the Ministry of Primary Industries; the directors of Mainzeal and the former directors of CBL Insurance.

While class actions in New Zealand remain relatively rare, they are increasing in number.

New Zealand is not Australia, however, and important differences remain. New Zealand is a much smaller market and claims are commensurately smaller, so they are less likely to justify an investment by lawyers and funders. New Zealand has activist regulators in the NZX and the Financial Markets Authority which investigate and seek remedies for continuous disclosure breaches and other securities breaches rather than leaving them to private lawyers and funders. It may discourage private litigants when the regulators do not view a case as worthwhile. New Zealand does not yet have a sophisticated class action regime – the Law Commission’s reform project has been on the back burner for more than twenty years and recent efforts to revive it have stalled repeatedly. Dual-listed companies are not as exposed to Australian litigation as it might appear, as they are obliged to comply with New Zealand laws rather than Australian laws and litigation against them is likely to need to be brought in New Zealand. These and other features mean that New Zealand is less able to support a community of lawyers who specialise in claims of this nature. While there have been recent high-profile actions such as the proceedings against the Mainzeal directors, they tend to be liquidators’ actions that have traditionally been funded in any event.

A fourth reason is the reduction in capacity in insurance markets for D&O risk. Lloyd’s of London has traditionally issued a large proportion of the higher ‘layers’ of high value New Zealand D&O policies, where the primary layer has been written locally and excess layers have been written out of London. This capacity is reducing as Lloyd’s has increasingly required its syndicates to demonstrate their solvency and their ability to operate profitably. This has resulted in a reduction of capacity and a corresponding reduction in availability of cover and increasing premiums.

Other liability risks are perceived as increasing. Regulatory actions against companies and directors appear to be on the increase, with the FMA being increasingly well funded and well staffed. The FMA’s focus remains on the conduct of directors and senior management. Following its Bank Conduct and Culture review of November 2018, the FMA and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand said that they would be:

“.. expecting to see much deeper accountability of boards, executives and senior managers. We will be looking for progress and clear evidence of change and want to see this become part of the ethos of all banks in New Zealand.”

New risks are also emerging which are difficult to predict. In a recent article, three judges of the New Zealand Supreme Court, writing on Climate Change and the Law, addressed directors’ risks with the following statement:

Directors have a duty to consider the “best interests” of the company in all of the colloquium jurisdictions. It remains to be seen how climate change impacts that duty. As we discuss below, there have already been cases in Australia and the United Kingdom relying on corporate governance and company law to hold companies to account for their climate impacts and actions.

While acknowledging that New Zealand companies legislation does not expressly require directors to consider the impact of operations upon the environment, the judges said that:

As a material financial risk, directors are accountable under care and diligence duties to take account of the financial consequences of climate change and this applies whatever model of corporate governance is subscribed to. Further, the “business judgement rule” would not protect directors where the legal risk stems from inadequate information or lack of inquiry.

What companies may do

Insurers need to understand the specific risks that a company and its directors face and how they are managing those risks, to build confidence that they may accurately assess the risk of losses.

We have seen positive outcomes where companies and their directors have presented insurers with a well-considered statement of the risks they face and how they are addressing them, with an explanation, if appropriate, of why those risks are not viewed as comparable with those faced by companies in Australia or elsewhere. We find that insurers often assume initially that New Zealand companies face the same risks as their Australian or other overseas counterparts, when this is not the case. In some instances, companies have managed increases in their premiums by withdrawing from areas of business that insurers are likely to view as unduly risky.

In some instances, brokers have managed premium increases by arranging reductions in cover limits where the risk of claims that exceed those limits is low. One technique that has had some success is to introduce shared limits across a number of policies. Where, for instance, it is unlikely that an event would result in a claim under both a Professional Indemnity and a Statutory Liability policy, it may be possible to agree with an insurer that those policies will share the same global limit. This reduces the insurer’s perception of its exposure and its actuarial assessment of risk and cost, resulting in only a small reduction in cover in real terms.

A similar approach that has been considered on an industry-wide basis or for large concerns with assets that are geographically widespread is to reduce cover to less than the total value of all risks that need to be insured, on the assumption that no event could result in a loss to all of the assets. Where, for instance, property is spread throughout New Zealand, it is very unlikely that a single earthquake or fire or tsunami could damage it all. A similar approach could perhaps be considered for D&O insurance on an industry basis. Inventive solutions such as these may need to be adopted if D&O cover is to remain affordable.